From Prison to "Freedom": Slavery as Best Business Practices

Employment opportunities for formerly justice-involved folks are limited, and introduce disparities leading to recidivism and major obstacles hindering reintegration into society.

Happy Belated Labor Day!

As most holidays originate from good intentions, we can identify two things about Labor Day: First, that a day dedicated to labor movements can assist in acknowledgment of past efforts to create beneficial changes in regards to workers rights. Secondly, we use these data points from a historical context to assist in creating a guiding narrative of how to orient others to the current direction in which labor movements are requiring continued revolution.

With all due respect to the full historical nature of the United States’ history of labor, I’ll provide a rapid reflection of the first two dates on the timeline I’ve referenced as a source of orientation for this post.

1607 - The colony at Jamestown identified a labor shortage, not having enough hands to provide necessary support. (VCU, 2015)

1619 - The slave trade achieved a goal of importing the first slaves into the colonies.

This is surprisingly enough historical context of the establishment of labor pre-constitution for us to be completely oriented in how to proceed with initiating a new labor movement. If you’re interested in learning more about the history of labor movements in the United States, check out the Labor History Timeline 1607 - 1999, from Virginia Commonwealth University’s Social Welfare History Project.

By defining colonization, we can fairly assess the cultural and moral guiding principles surrounding the establishment of the original 13 colonies and any causal influence in the signing of the Constitution. Colonization is the subjugation of a people or area, especially as an extension of state power (“Colonization,” 2025).

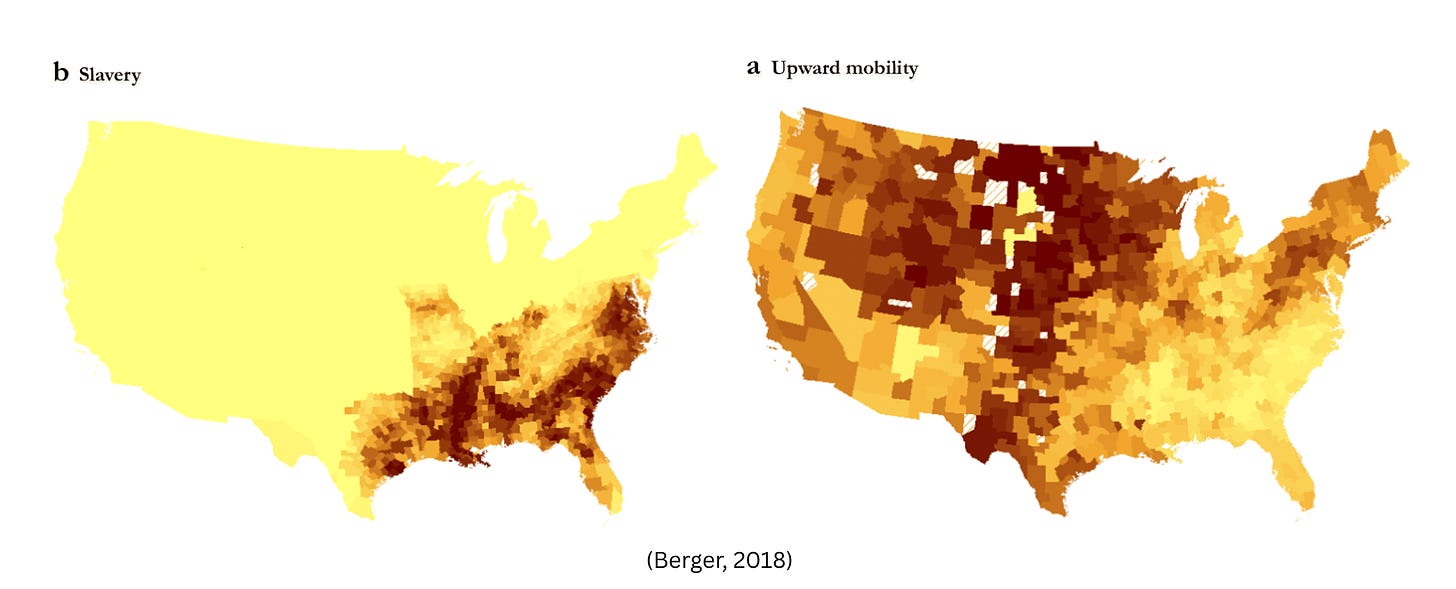

Fast-forward in time to just before the beginning of the Civil War, with the collection of slavery-related information in the census of 1860. Areas with the highest concentration of slavery during that time continue to be severely impacted by limited upward mobility when compared to areas with less slavery (Berger, 2018).

Impacts of slavery on current arrest rates show significant direct and indirect associations (Ward, 2022). Directly, for every 10% increase in slave concentration, an area has a 1% increase in disparity for Black arrests for violent offenses. This is closely mirrored in drug related arrests. Indirectly, as the White-Black unemployment ratio decreased, the Black-White arrest disparity increased. White economic superiority was perceived as a threat when equitable job opportunities were created, and subsequently punitive practices were implemented as a form of social control.

When President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, he effectively changed the legal status for slaves from enslaved to free. Actively fighting in the civil war during this time, there was reason for both sides to find a suitable compromise. Congress worked to create an amendment that would satisfy values on both sides of the battlefield to officially end the war.

Thirteenth Amendment of the Constitution of the United States

Section 1

Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

Section 2

Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation (U.S. Const. Amend. XIII.)

The Thirteenth Amendment of the Constitution was ratified by the states and certified on December 18, 1865. Slavery immediately became enforceable as punishment for crime. This effectively satisfied the Union’s desire to end the war and provided Confederates a legal framework to enforce involuntary servitude. Not only was it possible for previously enslaved individuals to be arrested for a crime and readmitted into slavery, it also allowed for anyone to enter into slavery regardless of race or country of origin. Introduction of this amendment made slavery enforceable for anyone convicted of a crime.

Looking forward to newfound freedom when being released from jails and prisons can be exciting, but most discover life after incarceration to be less than ideal. To maintain a home and family life, financial stability is required, necessitating employment to pay for rent or a mortgage. Current best hiring practices severely limit any individual with a criminal background from acquiring employment in most occupations, providing an obstacle to receiving pay ranges comparable to pre-incarceration.

Hiring practices haven’t always been as discriminatory as they currently are. Prior to the turn of the 20th century, employers took an applicant’s word in good faith for the hiring process (History of Background Checks, 2020). This shifted in 1908, when an employer was found liable for allowing an employee to remain employed after they were observed continually engaging in reckless behavior. The recklessness didn’t end until a coworker was killed during a prank. Negligent hiring law was instated, mandating employer responsibility for their employee’s behavior on the job.

Negligent hiring law expanded in the subsequent few decades to include hiring practices and identifying risks before employment. Employers were being held liable for any illegal conduct within the workspace. If an employee is hired and acts unlawfully, it is identified as employer negligence if the company doesn’t try to uncover an applicant’s background pre-employment. If an employer does discover a criminal background, they only consider the applicant 40% of the time compared to 90% likelihood of consideration for an individual receiving welfare (J. Holzer et al., 2003).

The translation of negligent hiring into Latin is respondeat superior, meaning “let the master answer” (Fay & Patterson, 2017). Suffice to say, the master-slave reference points to passive enforcement practices, transferring liability from an individual’s decisions to an employer’s judgement during the hiring process. This allows the opportunity for employer to perform legally standardized background checks to offset the cost of their liability if they hire someone with a criminal background who commits a crime at work.

Within two worlds, 1) Reentry from justice involvement, and 2) Restorative Justice, we identify how to approach true equality for individuals and their potential for success in society. Putting into practice frameworks that contradict societal conventions can prove challenging, but the literature backs it up. In the limited number of states actively addressing discriminatory negligent hiring practices, the data is clear. Increasing employment by 5-9% for individuals previously justice involved decreases criminal involvement and recidivism by 10% (Pyle, 2023).

It is here we continue the fight for liberation from systems of oppression. By identifying voice and aligning vision, our goals as individuals and organizations can coincide with that of previously justice involved folks as humans rather than the identification placed on them by an event that occurred on the worst day of their lives. We can then also offer restorative opportunities for mind and body integration for individuals and communities to allow society to flourish with a framework of humanitarianism rather than flounder under punishment.

It’s time for a labor movement focused on decreasing stigmatization and unjust practices within hiring. Why are background checks not only legal, but expected and mandated by employers? What has allowed for this type of treatment and penalization to be practiced, even when an individual has completed their judge-mandated time served? Are we complacent with people being judged by an incident for the remainder of their lives? And when is it that We The People stand up for those who need Justice for the injustices they’re experiencing post-incarceration? It’s about time we end mass slavery in the United States. If we’re not identifying this as perpetuated by employer best practices, we are doing a disservice to those who need our help the most.

References

Berger, T. (2018). Places of Persistence: Slavery and the geography of intergenerational mobility in the United States. Demography, 55(4), 1547–1565. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-018-0693-4

Colonization. (2025). In Merriam-Webster Dictionary. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/colonization.

Fay, J. J., & Patterson, D. (2017). Preemployment screening. In Elsevier eBooks (pp. 275–300). https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-809278-1.00014-1

History of background checks. (2020, April 24). Peopletrail. Retrieved September 12, 2025, from https://peopletrail.com/history-of-background-checks/

Holzer, H. J., Raphael, S., & Stoll, M. A. (2003). Employment Barriers Facing Ex-Offenders. In Urban Institute Reentry Roundtable. New York University Law School. Retrieved September 12, 2025, from https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/59416/410855-Employment-Barriers-Facing-Ex-Offenders.PDF

Labor History Timeline: 1607 – 1999. (2015, October 28). Social Welfare History Project. https://socialwelfare.library.vcu.edu/organizations/labor/labor-history-timeline-1607-1999/

Pyle, Benjamin D., Negligent Hiring: Recidivism and Employment with a Criminal Record (2023). Available at: https://scholarship.law.bu.edu/faculty_scholarship/3633

U.S. Const. Amend. XIII.

Ward, M. (2022). The legacy of slavery and contemporary racial disparities in arrest rates. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, 8(4), 534–552. https://doi.org/10.1177/23326492221082066